George Hoyningen-Huene, Portrait of Horst, 1931

A mild case of tuberculosis brought Horst's public school days to an end. He spent a year in a sanatorium in Switzerland in the early 1920s. After briefly studying Chinese in Frankfurt am Main, he worked in an import-export firm as a file clerk. Introduced to the arts by his paternal aunt, Horst longed to find a way into that world. He was particularly fascinated by the Bauhaus. Initially interested in architecture, Horst entered the Kunstgewerbeschule in Hamburg to design furniture. In 1930, he moved to Paris where was accepted by Le Corbusier as an apprentice in the Bauhaus architect's studio.

While at a Parisian café, Horst met Baron George von Hoyningen-Huene, a Russian emigrant and photographer for Vogue magazine. Influenced by Huene, who became his lover, Horst abandoned architecture in favor of photography. He worked as an assistant and occasional model for Huene. Through him, Horst met fashion photographer Cecil Beaton and Vogue art director Mehemed Agha. In 1931 Agha invited Horst to the Vogue studio in Paris to learn how to photograph fashion models. Initially, Horst's work echoed the cool classicism of Huene, with plain or geometric backgrounds, artificial lights that emphasized chiaroscuro, and an occasional reference to ancient Greek or Roman sculpture.

Horst's first pictures appeared in the December 1931 issue of French Vogue. It was a full-page advertisement showing a model in black velvet holding a Klytia scent bottle in one hand with the other hand raised elegantly above it. Horst's real breakthrough as a published fashion and portrait photographer was in the pages of British Vogue starting with the 30 March 1932 issue showing three fashion studies and a full-page portrait of the daughter of Sir James Dunn, the art patron and supporter of Surrealism.

Horst P. Horst, Bending Nude, 1941

In 1932, Horst held his first exhibition in Paris. After a brief period of freelancing, he was hired by Vogue in 1935 after the temperamental Huene quit the magazine. His affair with Huene over, Horst became involved with Luchino Visconti, the Italian aristocrat who was to become an important filmmaker. In 1938, Horst met British diplomat Valentine Lawford, who became his longtime companion and biographer. The two remained together until Horst's death. The 1930's were an exciting time for Horst. His work was published and exhibited in both America and France. His circle of influential friends grew to include artists such as Jean Cocteau, and fashion designer Coco Chanel whom he called "the queen of the whole thing". He would photograph her fashions for three decades.

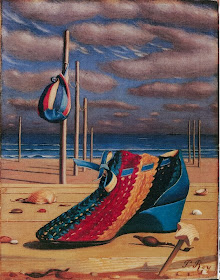

Horst P. Horst, Electric Beauty, 1939

Electric Beauty (above) dates from 1939, the year in which Europe entered the Second World War. With its backdrop relating to Hieronymus Bosch's Temptation of Saint Anthony, it goes beyond a depiction of the more surreal aspects of the fashion industry to communicate a sense of impending menace. Horst left for America in late summer of 1939, shortly after taking what would be one of his most enduring images - of a model, bathed in deep shadows, wearing an unraveling corset. He said the Mainbocher Corset summed up his feelings about an era's end. ''While I was taking it,'' he said, ''I was thinking of all that I was leaving behind.''

When war was declared between America and Germany on 7 December 1941, Horst was called up for service, though he was not officially enrolled until July 1943. The late 1930s and early 1940s were his most productive years. As a typical example of wartime escapism, the Rita Hayworth film Cover Girl (1944) provided Horst with the opportunity to produce one of his most sumptuous film-star covers in a montage of seven different portraits of the cover girl Susann Shaw set against a silk design. His picture of Loretta Young became an almost immediate classic when it was featured in a special edition of Vogue which included masterpieces of photography selected by Edward Steichen to show off the first hundred years of the medium.

He went on to have a successful career as a photographer for American Vogue, though, in the 1960's, when editors demanded more lifelike shots of models running and skipping, he fell out of favor. In the 1980s, the dramatic pre-war photographic style became popular again, and Horst enjoyed a rejuvenation of his career. Synonymous with the creation of images of elegance, style, and glamour, he was sought out by such stars of the 1980s as pop group Duran Duran. Horst' career can be said to have reached Old Master status when pop goddess Madonna created her celebrated hymn to classic fashion photography with her single Vogue in 1990. In the video directed by David Fincher, she posed as a recreation of Horst's most iconic fashion image, a model seen from behind, wearing a partially tied, back-laced corset made by Detolle.

Failing eyesight and poor health marred Horst's last years. He died at his home in Palm Beach Gardens, Florida on November 18, 1999. You can see more works of him on his official website.