Hannah Höch with her Dada Dolls, 1920

Hannah Höch (1889-1978) was born in Gotha. Her father was the director of an insurance company, her mother a hobby painter. Hannah studied at the Kunstgewerbeschule (Arts and Crafts School) in Berlin between 1912 and 1915. She finished her studies under Emil Orlik, concentrating on collage techniques. After her schooling, she worked in the handicrafts department for the Ullstein publishing house, designing dress and embroidery patterns for Die Dame (The Lady) and Die Praktische Berlinerin (The Practical Berlin Woman).

Hannah Höch, The Puppet Balsamine, 1927

She met Dadaist Raoul Hausmann in 1915 and they became close friends. Höch was the only woman participating in the First International Dada Fair which took place at at Dr. Otto Burchard’s Berlin art gallery in July 1920. Among her fellow dadaists were Johannes Baader, George Grosz and John Heartfield. Höch's personal relationship with Hausmann grew from friendship to a temptous romance over time, but they separated in 1922, partly because Höch didn't like Hausmann's insistence on an "official" ménage à trois together with his wife (Hausmann's dream came true in the late 1920s, when he moved with his wife Hedwig and his model Vera Broido to the fashionable district of Charlottenburg).

Raoul Hausmann, Double Portrait Hannah Höch and Raoul Hausmann, c. 1920

Hannah Höch - by now living with a woman, Dutch writer Til Brugmann, left a sketch of Hausmann around 1931: "After I had offered to renew friendly relations we met frequently (with Til as well). At the time he was living with Heda Mankowicz-Hausmann and Vera Broido in Kaiser-Friedrich-Straße in Charlottenburg. Til and I went there often. But I always found it very boring. He was just acting the photographer, and the lover of Vera B, showing off terribly with what he could afford to buy now - the ésprit was all gone."

While the Dadaists paid lip service to women's emancipation they were clearly reluctant to include a woman among their ranks. The filmmaker Hans Richter described Höch's contribution to the Dada movement as the "sandwiches, beer and coffee she managed somehow to conjure up despite the shortage of money." Raoul Hausmann even suggested that Höch get a job to support him financially. Later, Höch ironized the hypocrisy of the Berlin Dada group in her photomontage The Strong Guys:

Hannah Höch, Die starken Männer (The Strong Guys), 1931

Höch observed in an undated note: "None of these men were satisfied with just an ordinary woman. In protest against the older generation they all desired this "New Woman" and her groundbreaking will to freedom. But - they more or less brutally rejected the notion that they, too, had to adopt new attitudes. This led to these truly Strindbergian dramas that typified the private lives of these men".

Höch was one of the forerunners in criticising society in the form of photomontages, a technique she developed in 1919. Her most famous piece became Schnitt mit dem Küchenmesser DADA durch die letzte Weimarer Bierbauchkulturepoche (Cut with the Dada Kitchen Knife through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch), a critique of Germany in 1919. Perhaps it was the training at Ullstein that facilitated Höch’s finely-tuned eye for both snipping and re-assembling, which is so amply on display in Cut with the Kitchen Knife:

Hannah Höch, Cut with the Dada Kitchen Knife through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch, 1919

Another brilliant and utterly ironic collage from 1919 (below) shows Friedrich Ebert (middle), first President of the Weimar Republic and his "bloodhound", defence minister Gustav Noske (right above), who was responsible for the assasination of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht earlier that year. Both men are depicted in bathing suits with a fig leave - a symbol of innocence - before their bellies. The collage also refers to the so-called "bathing suit affair": After the liberal Berliner Illustrierte had printed a photo of Ebert and Noske in bathing suits, the right-wing press (which, a couple of months earlier had celebrated the assasinations of Luxemburg and Liebknecht) started a campaign against the "obscene behaviour" of the two statesmen.

Hannah Höch, Dada Panorama, 1919

An exciting work during the mid 1920s was the ambitious From the Ethnographic Museum series, 17 works that constitute an epic foray into the notion of alien cultures and female identity (see Imaginary Bride below). It was visually influenced by the newly-redone tribal art displays in Berlin's Ethnological Museum.

Hannah Höch, Imaginary Bride, 1926

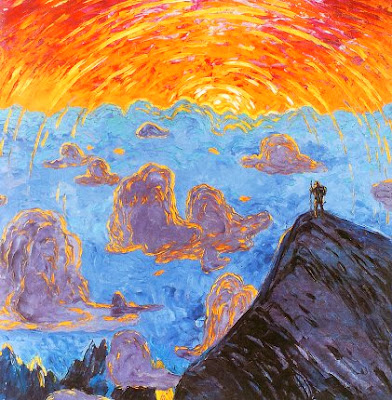

Around 1920, the woman was for many artists the "eteral woman" or "world mother" - either a subject of their male salvation fantasies, or an object of morbid desires. Oskar Kokoschka spooned with dolls and imagined his Murderer, The Hope of Woman, Dix painted his Moon Woman, and Otto Freundlich anchored "The Mother" in the world of ideas of his cosmic communism. Marcel Duchamp built Bachelor Machines, Kurt Schwitters designed his Merzbau as a "cathedral of erotic misery", and Rudolf Schlichter's yearning for boots remained unsatisfied because he got the whole woman instead. And Höch painted Associations. In the center of the picture she placed two intertwined plant-like structures, engaged in a process of fertilization, whose blossoms are made of machine parts:

Hannah Höch, Vereinigungen (Associations), 1929

Höch’s focus on the nature of female identity (and its depiction in the media) reached a crescendo in the early 1930s in works like Tamer (below). Most probably Tamer relates to her new life with Til Brugman (they were together from 1926 to 1936). It represents the general move toward increasing gender ambiguity in Höch’s imagery, as can also be seen in her self-portrait Russian Dancer.

Hannah Höch, Tamer, 1930

Höch made many influential friendships over the years, with Hans Arp and Kurt Schwitters among others. She met Theo van Doesburg and Piet Mondrian in 1924 in Paris, and a trip to Holland in 1926 was extended to a stay of three years. Here, in 1926, she met and grew to love Til Brugmann. The relationship, scandalous as it was for the time, sharpened her eye to the allocation of male and female roles. Höch and Brugmann returned to Germany in 1929, and she participated in two important exhibits: The prestigious Film and Photo exhibition, the first big photography show in Europe, included 18 of her photomontages. Some 10.000 people saw the exhibition on its first tour stop alone, Stuttgart. In that year, the De Bron Gallery in The Hague mounted her first one-woman show, which included her oil paintings, numerous drawings, and watercolors, though not her photomontages.

Hannah Höch, The Journalists, 1925

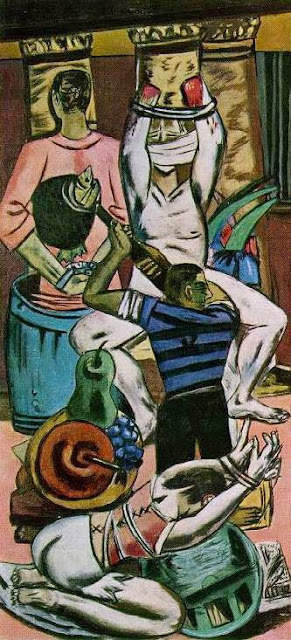

Höch’s public career as an artist was launched. Other exhibitions followed - in 1931 at Berlin’s Kunstgewerbemuseum; and in 1932 at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and at the Palais des Beaux Arts in Brussels. The Bauhaus mounted a show of 15 of her photomontages later that year. This public recognition came to an end in 1933, when Adolf Hitler seized political power. Like all avantgarde artists, Höch and her circle were deemed "Cultural Bolshiviks" and "Degenerates" by the National Socialist régime. Höch refused to support the Nazis, and continued to secretly produce critical works like the The Mockers (you can see that she was a brilliant painter too):

Hannah Höch, The Mockers, 1935

As the 1930s wore on, Höch’s world became increasingly dangerous. She expressed her feelings of loneliness and isolation in her painting The Fear (below). Höch married the much-younger businessman and pianist Kurt Matthies in 1938 and divorced him in 1944. In September, 1939, a few days after the begin of the Second World War, she moved to the relative obscurity of Heiligensee, a remote suburb of Berlin. She felt lucky to have found a place where "nobody would know me by sight or be aware of my lurid past as a Dadaist".

Hannah Höch, Angst (Fear), 1936

After the end of the war, Höch was one of the first to actively revive artistic life in Berlin and to contribute to the gradual recovery of German art after the war. In 1945, she put together her Bilderbuch (Picture Book), a photomontaged zoological garden populated with Brushflurlets (below) as well as other strange creatures, and accompanied by a series of sly, silly poems like Unsatisfeedle:

Flailing his arms about, quite a sight,

He had wanted the black dress

But God gave him the white.

So with his sourpuss

he lives out his life.

He nurtures the eccentricity

it’s the wrong one — explicitly.

Bilderbuch wouldn’t be published in its entirety until 1985, six years after Höch’s death, and then only in a limited edition of 200. Now, Berlin publishing house The Green Box has rescued this unique volume from out-of-print obscurity with a lovely facsimile edition that reproduces the poems in English translation. During the 1950s and 1960s, Höch produced abstract works but also a large number of highly acclaimed colour collages, which transformed reality in an ironic and fantastic manner:

Hannah Höch, Grotesque,1963

Höch exhibited works at the large Dada exhibitions such as at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1948 and at the Kunsthalle Düsseldorf in 1958. Other exhibitions in London and Paris followed. An important retrospective exhibition of Höch's work was organised in 1973 in Paris and then toured to her hometown Berlin. Höch died in 1978 at the age of 88 years in her house in Berlin-Heiligensee.