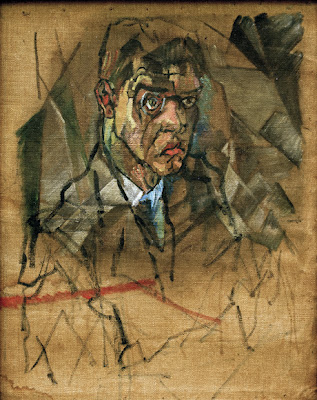

Conrad Felixmüller, Portrait of Raoul Hausmann, c.1920

Raoul Hausmann (1886-1971) was born in Vienna to Gabriele Hausmann, née Petke, and the Hungarian portrait and history painter Victor Hausmann. In 1900, Raoul moved with his family to Berlin. He left school at the age of fourteen and began artistic studies with his father instead. "My childhood was rather happy, because my parents didn't care about my private life. My father was very liberal. My mother was a beautiful lady, very distant and alien", Hausmann remembered shortly before his death. His parents committed suicide in 1920.

Raoul Hausmann, Psychogramm, 1917

In 1905, Hausmann met the violinist Elfriede Schaeffer, whom he married after the birth of their daughter Vera in 1907. Between 1908 and 1911, Hausmann enrolled at Arthur Lew-Funcke's art school, one of the many private art schools in Berlin, where he studied anatomy and nude drawing. He worked on his first typographical designs as well as glass window designs, and assisted his father with the restoration of murals in the Hamburg city hall in 1914. One year later, Hausmann began an extramarital affair with the artist Hannah Höch, forming an artistically productive yet turbulent relationship that would last until 1922.

Raoul Hausmann, Portrait of Hannah Höch, 1916

Hausmann's encounters with expressionist painting in 1912 (which he saw in Herwarth Walden's avant-garde Sturm Gallery), proved pivotal for his artistic development. He produced his first expressionist lithographs and woodcuts in Erich Heckel's atelier and published his first polemical texts against the art establishment in Walden's magazine, also named Der Sturm. Hausmann remained active in expressionist circles well into 1917, publishing two essays in Franz Pfemfert's Die Aktion, a journal known for its leftist, antimilitaristic stance. As an Austrian-born citizen living in Germany, Hausmann was not drafted into military service and thus was spared the shattering war experiences that affected the work of so many artists. Yet his initial attitude toward the war was characteristic of the expressionist generation in that he believed the devastation on the battlefields held promise of a vital future, destroying calcified Wilhelminian social structures and clearing the way for a new world.

Raoul Hausmann, Self-Portrait, c. 1920

In 1916, Hausmann met the two men whose radicalism nourished this idea of a new beginning, namely the psychoanalyst Otto Gross, an anarchist and early disciple of Siegmund Freud, who considered psychoanalysis to be preparatory work for a revolution. He also befriended the radical writer Franz Jung, who was a disciple of Gross (and avid reader of Walt Whitman). Inspired by the work of Gross and Jung, as well as the writings of Whitman and Friedrich Nietzsche, Hausmann understood himself to be a pioneer for the birth of the new man. The notion of destruction as an act of creation was the point of departure for Hausmann's Dadasophy, his theoretical contribution to Berlin Dada.

Raoul Hausmann's Postcard to I.K. Bonset, 1921

Hausmann was one of a group of young radicals that began to form the nucleus of Berlin Dada in 1917. Richard Hülsenbeck ("To make literature with a gun in my hand had for a time been my dream") delivered his First Dada Speech in Germany, January 22, 1918 at the fashionable Neumann gallery on Kurfürstendamm. Over the course of the next few weeks, Hausmann, Hülsenbeck, George Grosz, John Heartfield, Franz Jung, Hannah Höch, Walter Mehring and Johannes Baader started the Club Dada. The first event staged was an evening of poetry performances and lectures against a retrospective of paintings by the "established" artist Lovis Corinth at the Berlin Sezession, April 12th, 1918: Hülsenbeck recited the Dada Manifesto, Grosz danced a Sincopation Jazz, whilst Hausmann ended the evening by shouting his manifesto The New Material in Painting at the by-now near riotous audience. The Berliner Börsen-Courier, a conservative newspaper reported:

"The threat of violence hung in the air. One envisioned Corinth's pictures torn to shreds with chair legs. But in the end it didn't come to that. As Raoul Hausmann shouted his programmatic plans for dadaist painting into the noise of the crowd, the manager of the sezession gallery turned the lights out on him."

Cover of Der Dada, Vol. 1, including a poem, Dadadegie, by Johannes Baader and Raoul Hausmann, 1919

As Dadasoph, and cofounder of Club Dada in Berlin, Hausmann wrote several key Dada texts, including the "Dadaist Manifesto" with Richard Huelsenbeck and the sixteen-page Club Dada brochure with Jung and Huelsenbeck. He also edited the journal Der Dada (above). The periodical contained drawings, polemics, poems and satires, all typeset in a multiplicity of opposing fonts and signs. From 1919 onward, Hausmann prepared the big world atlas Dadaco, though the project fell through due to editorial difficulties. In addition, Hausmann played a central role in organizing Dada events, including the First International Dada Fair with John Heartfield and George Grosz and numerous Dada matinees and soirées in Berlin, often in collaboration with Johannes Baader.

Raoul Hausmann, Dada wins!, 1920

At the beginning of 1920, Baader (Chief-Dada), Hausmann (Dadasopher) and Huelsenbeck (World-Dada) embarked on a six week tour of Eastern Germany and Czechoslovakia, drawing large crowds of up to 2000 people and bemused reviews. The programme included primitivist verse, simultaneous poetry recitals by Baader and Hausmann, and Hausmann's Dada-Trot (Sixty-One Step) described as "a truly splendid send-up of the most modern exotic-erotic social dances that have befallen us like a plague." Hausmann's artistic contributions to Dada were purposefully eclectic, consistently blurring the boundaries between visual art, poetry, music, and dance. His "optophonetic" poems of early 1918 fused lyrical texts with expressive typography, insisting on the role of language as both visual and acoustic. Boisterous public performances of these poems not only underscored their vocal dimension but also transformed their two-dimensionality into a bodily experience. You can here some of his acoustic poems on UbuWeb; a few are even on sale at iTunes.

August Sander, Raoul Hausmann, 1920s

From 1918, Hausmann incorporated collage elements into his work, influenced by war photomontages from the front that he saw while on vacation with Hannah Höch. He also manufactured several reliefs and assemblages. The most famous work, Der Geist Unserer Zeit - Mechanischer Kopf (The Spirit of Our Age - Mechanical Head) was constructed from a hairdresser's wig-making dummy. The piece has various measuring devices attached including a ruler, pocket watch mechanism, typewriter, camera segments and a crocodile wallet:

Raoul Hausmann, The Spirit of Our Age - Mechanical Head, 1920

In September 1921, Hausmann, Höch, Kurt Schwitters and his wife Helma undertook an "anti-dada" tour to Prague. As well as his recitals of sound poems, he also presented a manifesto describing a machine "capable of converting audio and visual signals interchangeably, that he later called the Optophone" (after many years of experimentation, this device was patented in London in 1935). By the late 1920s, Hausmann had re-invented himself as a fashionable society photographer, and lived in a ménage à trois with his second wife, painter Hedwig Mankiewitz, and his new love Vera Broido in the fashionable district of Charlottenburg.

Raoul Hausmann, Two Nudes on a Beach [Hedwig Mankiewitz and Vera Broido], 1930

Vera Broido was born in St Petersburg in 1907, the daughter of two Russian Jewish revolutionaries. In 1914, when Vera was seven, her family was plunged into a life of isolation and fear when her mother, Eva Broido, was sentenced to exile in Western Siberia for taking a stand against the war. Vera fled Siberia for Paris (where she studied under Alexandra Exter), and then moved on to Berlin. She never saw her mother Eva again and was later told that she had been executed.

Raoul Hausmann, Study of Expression [Vera Broido], 1931

After his engagement with Dada, Hausmann now focused primarily on photography, producing portraits, nudes, and landscapes. After the Nazis had seized power in January of 1933, Hausmann, his wife and Vera Broido emigrated to Ibiza. The photographs he produced focused on ethnographic and architectural motifs of premodern life in Ibiza. After the outbreak of the the Spanish Civil War in 1936, and the bombardment and subsequent occupation of Ibiza by Franco's troops, Hausmann (who had been active in Spanish anti-fascist groups) had to leave Ibiza. After an adventureous voyage he shortly settled in Prague, but was forced to flee again in 1938 after the German invasion of Czechoslovakia. He then moved to Peyrat-le-Château, near Limoges where he lived illegally with his Jewish wife Hedwig, hiding for years in a small and humid rooftop chamber. After the Normandy landings in 1944, the pair finally moved to Limoges, where Hausmann lived in a secluded manner for the rest of his life.

The First International Dada Fair at Dr. Otto Burchard’s Berlin art gallery in 1920. From left to right: Hausmann, Höch, Dr. Burchard, Baader, Herzfelde, Margarete Herzfelde, Schmallhausen, Grosz (with hat and cane), Heartfield.

In the 1950s there was a revival of interest in Dada, especially in the United States. As interest grew, Hausmann began corresponding with a number of leading American artists, discussing Dada and it's contemporary relevance. He refuted the term Neo-Dada, then in vogue, which had been applied to a number of artists including Yves Klein, Robert Rauschenberg, and George Maciunas, to whom he wrote in 1962:

"I think even the Americans should not use the term "neodadaism" because "neo" means nothing and "ism" is old-fashioned. Why not simply "Fluxus"? It seems to me much better, because it's new, and dada is historic. I was in correspondence with Tzara, Hülsenbeck and Hans Richter concerning this question, and they all declare neodadaism does not exist. So long."

Adrian Ghenie, Dada is Dead, 2009

Raoul Hausmann died in Limoges on February 1, 1971. So long.