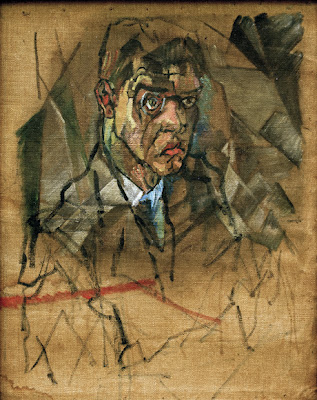

El Lissitzky, Kurt Schwitters, 1924

Kurt Schwitters (1887-1948) was born in Hanover, Germany, to a well-to-do family. His parents were owners of a ladies' wear shop. From early childhood Schwitters suffered from epileptic seizures, later he said that these experiences led him to art. He attended the Kunstakademie in Dresden from 1909 to 1914 (alongside with Otto Dix and George Grosz). Schwitter's early paintings were mostly landscapes and academic portraits. In 1915 he married Helma Fischer, a teacher. Schwitters began to construct his first Merzbau in 1915, the transformation of six (or possibly more) rooms of the family house in Hannover, Waldhausenstrasse 5. This took place very gradually. Early photos show the Merzbau with a grotto-like surface and various columns and sculptures, possibly referring to similar pieces by Dadaists, including the Great Plasto-Dio-Dada-Drama by Johannes Baader, shown at the First International Dada Fair, Berlin, 1920. Works by Hannah Höch and Raoul Hausmann, amongst others, were incorporated into the installation.

Kurt Schwitters, The Cathedral of Erotic Misery - Merzbau - Hanover - 1924

Using wood and plaster for the basic structure of the cubistic assemblage, which also included carboard, scraps of metal, old furniture, leftover objects found in garbage bins, and items from his friends, such as Mies van der Rohe's pencil and Sophie Täuber-Arp's brassière. "Everything an artist spits out is art," Schwitters said. The word "Merz" has a variety of associations, starting from "Kommerz" (commerce) to Schmerz (pain) and ausmerzen (to discard). With "Merz", Schwitters defined his own unique movement, "in close artistic friendship with Core dadaism," as he wrote. After the death of his son Gerd, he incorporated his death mask in the Merzbau. Schwitters christened the gigantic work, which eventually extended through several floors and room, The Column and then as his Cathedral of Erotic Misery. Only the gallery owner and critic Herwarth Walden, the architectural historian Sigfried Giedion, and Hans Arp were allowed to see the most secret caves of the Merzbau. His visitors Schwitters greeted with his own onomapoetic language - "the language of the birds" - while sitting on a tree branch.

Kurt Schwitters, Merzbau, reconstruction by Peter Bissegger 1981–3 (Sprengel Museum Hanover)

Schwitters was to come into contact with Herwarth Walden after exhibiting expressionist paintings at the Hanover Secession in February 1918, which led directly to meetings with members of the Berlin Avant-garde, including Raoul Hausmann, Hannah Höch and Hans Arp in the autumn of 1918. "I remember the night he introduced himself in the Café des Westens. 'I'm a painter', he said, 'and I nail my pictures together'", Raoul Hausmann later reported. Schwitter's poems and essays were published in Herwarth Walden's Der Sturm magazine. An Anna Blume (1919), Schwitters's first collection of verse, which appeared in the magazine, provoked a strong response. It parodied the high-flown language of love poetry, and was a critical and commercial success; it sold a 13.000 copies.

Cover of Anna Blume, Dichtungen, 1919

Hausmann Remembers

by Kurt Schwitters (c. 1920)

Then came Anna Bloom, and Kurt was famous.

"For all the wrong reasons, of course", he said,

but clearly, from his grin, he enjoyed it.

"For all the wrong reasons, of course", he said,

but clearly, from his grin, he enjoyed it.

Anna Bloom is out of her tree!

Anna Bloom is red.

What colour is the tree?

That's how a schoolboy teases his sweetheart,

not satire at all; and in this age

(so we dadas proclaimed) art must be savage

- a frontal attack!

But Kurt held a mirror up to dada

- reversed its sneer

to a laughing face.

He called our southern tour "Anti-Dada"

and added an "h" to my Hanna(h)'s name

so he could read her backward.

Anna Bloom is red.

What colour is the tree?

That's how a schoolboy teases his sweetheart,

not satire at all; and in this age

(so we dadas proclaimed) art must be savage

- a frontal attack!

But Kurt held a mirror up to dada

- reversed its sneer

to a laughing face.

He called our southern tour "Anti-Dada"

and added an "h" to my Hanna(h)'s name

so he could read her backward.

In 1920 Schwitters met Hans Arp, who introduced him to the new collage method, and made a lecture tour with Raoul Hausmann in Chechoslovakia. In 1922 he attended the Dada meeting in Weimar. However, Schwitters never became a friend of George Grosz, who once drove him from his door, saying "I am not Grosz." Schwitters replied after ringing the bell again: "I am not Schwitters, either." Grosz was rebellious and politically committed, Schwitters described himself ambiguously as "Bürger und Idiot" (Bourgeois and Idiot). Schwitters founded the Merz magazine in 1923; the last issue was published in 1932. Merz consisted of books, catalogues, poems and paitings. Numbers 14-17 contained children's books written by Schwitters, Kate Steinitz and Theo van Doesburg. You can see scans of the magazine here. Schwitters also composed and performed an early example of sound poetry, Ursonate. The poem was influenced by Raoul Hausmann's poem "fmsbw" which Schwitters' heard recited by Hausmann in Prague in 1921. You can hear it here.

Most of the works attempt to make coherent aesthetic sense of the world around Schwitters, using fragments of found objects. These fragments often make witty allusions to current events. Merzbild 29a, Picture with Turning Wheel (1920, below), for instance, combines a series of wheels that only turn clockwise, alluding to the general drift Rightwards across Germany after the failed Spartacist Uprising in January that year. Thanks to Schwitters' lifelong patron and friend Katherine Dreier, his work was exhibited regularly in the US from 1920 onwards. In the late 1920s he also became a well-known typographer. In 1928 Schwitters traveled in Norway, where he began to spend much of his time from 1931 onwards. In 1937, Schwitters was designated a "degenerate" artist by the Nazis and his works were shown in the Entartete Kunst exhibition. Schwitters left Germany for Norway, settling in Lysaker near Oslo. He never returned to the city of his birth. His wife Helma died of cancer in 1944 in Hanover.

When German troops invaded Norway, Schwitters fled in 1940 with his son for the United Kingdom on the ice breaker Fridtjof Nansen. Interned as an enemy alien by the British government he was held in interment camps for eighteen months. After being discharged from Hutchinson Square Camp at Douglas, Isle of Man, he settled in London. Schwitters had an exhibition in London in 1944 and in 1947 in New York and Basel, but his work did not attract significant popular or critical interest. Schwitters's Hanover Merzbau was completely destructed by Allied bombing raids on the night of October 8, 1943.

In 1944 a stroke left Schwitters temporally paralyzed on one side of his body. The next year he moved with Edith Thomas to Ambleside, in the Lake District. There he became a well known figure, although he did not talk about his past. His portraits of local residents were displayed in shops. With the financial aid from the Museum of Modern Art, New York, Schwitters began to build in 1947 his third Merzbau (or the Merzbarn) into a stone barn At Elterwater. He never finished it. Schwitters died in solitude on January 8, 1948, in Kendal. Many artists have cited Schwitters as a major influence, including Ed Ruscha and Robert Rauschenberg, who said after seeing an exhibition of Schwitters' work in 1959, that "I felt like he made it all just for me." You can read more about Kurt Schwitter's here.