On the table gaily set, behold, within the dish,

the fishes' queer countenance.

Fish are mute ... so one thought. Who knows?

Is there not a place where the language of the fish,

in their absence, is at last in common parlance?

Rainer Maria Rilke, The Sonnets to Orpheus, Part 2, XX

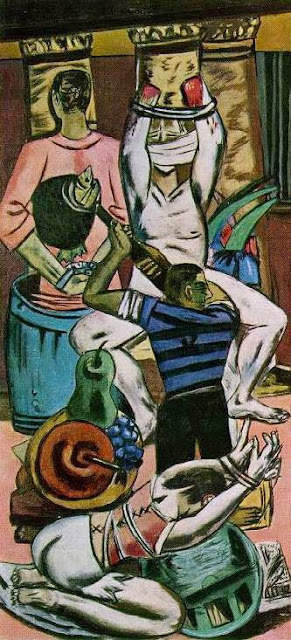

Max Beckmann, Journey on the Fish, 1933

After Hitler’s assumption of power in 1933, Beckmann lost his teaching position at the Städelschule in Frankfurt and was forced to retreat into private life. His painting Journey on the Fish (above) is the recognition of the 50-year-old that his destiny was now inevitably bound to that of his second wife Quappi. The doubling of the motifs - fish, persons, and masks (of which one shows Beckmann's profile, the other that of Quappi) - captures the theme of the linked pair. Joined in unity with two fish, the couple seems to stumble towards an abyss, although it is not clear whether they are headed for a black seashore or a dark chasm. The fish played a significant role in Beckmann’s work - as a symbol of phallus, fertility and animal nature. In this painting, the fish may be seen as the couple’s rescuer, leading them to new shores. The work is indicative of Beckmann's life circumstances at the time and a hint of his later emigration.

Max Beckmann, The Small Fish, 1933

Beckmann, a vivid reader of Schopenhauer, and connaisseur of Greek and Eastern mythology might also refer to the Semitic god Dagon, part man and part aquatic animal. In the eleventh century, the Jewish bible commentator Rashi commented that the name Dagon is related to Hebrew dag (fish) and that Dagon was imagined in the shape of a fish. In the thirteenth century rabbi David Kimhi interpreted the odd sentence in Samuel 5.2-7 that "only Dagon was left to him" to mean "only the form of a fish was left", adding:

It is said that Dagon, from his navel down, had the form of a fish, and from his navel up, the form of a man, as it is said, his two hands were cut off.

Beckmann's foresight employed the cut-off hand and fish symbol already in 1921:

Max Beckmann, The Dream, 1921

The fish form may also be considered as a phallic symbol as seen in Beckmann's The Small Fish (above) or in the story of the Egyptian grain god Osiris, whose penis was eaten by fish in the Nile after he was attacked by Set. Likewise, in the tale depicting the origin of the constellation Capricornus, the Greek god of nature Pan became a fish from the waist down when he jumped into the same river after being attacked by Typhon. John Milton used this myth in Paradise Lost:

Next came one

Who mourned in earnest, when the captive ark

Maimed his brute image, head and hands lopt off,

In his own temple, on the grunsel-edge,

Where he fell flat and shamed his worshippers:

Dagon his name, sea-monster, upward man

And downward fish; yet had his temple high.

Maimed his brute image, head and hands lopt off,

In his own temple, on the grunsel-edge,

Where he fell flat and shamed his worshippers:

Dagon his name, sea-monster, upward man

And downward fish; yet had his temple high.

Max Beckmann, Departure (left panel), 1933

Beckmann (who hated talking about his paintings) once responded to a reporter asking why he put fish into so many of his paintings: "Because I like fish, both to eat and to look at. Also they are symbols." What do they symbolize? "Geist - spirit," Beckmann replied. "But the man who looks at my pictures must figure them out for himself." It is interesting to note that the first thing Beckmann said is that he simply likes fish - to eat and to look at. That is a good response. We do, after all, eat fish. Why do we eat? To live, to have strength, and to have potency. As Chesterton implies through a character in The Napoleon of Notting Hill:

A man strikes the lyre, and says, "Life is real, life is earnest," and then goes into a room and stuffs alien substances into a hole in his head.

No comments:

Post a Comment